If you’ve been following this newsletter for a while and/or have known me for longer than two years, you’ll know that I co-founded a knitwear brand called Public Habit in 2019 with my close friend and son’s godfather. TLDR, we started making sourcing trips to China in 2018 to figure out the apparel supply chain with the intent of launching a DTC apparel company. Then I moved to China in 2018 with my husband and started really spending time in Tier 1 and 2 factories1 asking about their business models and what it would take to lower MOQs2. Naive and curious (the best combo for starting a new venture), what started as an experiment for testing and building high quality fitness and basics product lines on Amazon turned into something very different. You can learn a bit more about my story here.

We launched Public Habit in late 2019 with zero inventory and a fully on-demand production model, shipping directly from the factory to end customers worldwide. As you can imagine, this helped save a lot of money on domestic storage in the US from bringing in bulk goods. But, more than saving on storage costs, we were able to save about $20-30/unit on every sweater we sold because of de minimis tax exemption. This was a pretty new model at the time but now you can find it at the biggest instant fashion players of our day: SHEIN, Temu, Amazon and TikTok Shop. While we had pretty pure intentions to leverage this loophole - avoid bulk inventory, increase cashflow and eliminate overproduction - this loophole has enabled a veritable typhoon of small parcel shipments from (mostly) China to the West, tax free.

I’ve been a big proponent of on-demand production for several years (obvi) and love what companies like Unspun and PlatformE are doing. I also think it’s exciting to think about how other industries are informing the fashion industry so we can move from a push model to a pull model in the supply chain (make based on what’s ordered, not try and sell what’s already made). That being said, the purest form of on-demand production appears to be instant fashion and a barrage of cheap goods made in small quantities and flown across the world in small shipments, straight to your doorstep.

I love Merriam Webster’s definition of de minimis, a Latin phrase meaning:

“lacking significance or importance : so minor as to merit disregard.”

These “insignificant” shipments to the US alone have surged to 1.36 billion in 2024, growing nearly 10× in just nine years.

Many of us in the sustainability corner have been quietly hopeful that one unintended outcome of removing de minimis would hurt SHEIN and other instant fashion players like Temu and Amazon’s Haul. So, I’ve been curious to understand what the impact has actually been of removing this loophole. If SHEIN’s business model hinged on de minimis, wouldn’t it die a very quick death once those tax exemptions went away?

In short, it has helped slow down this juggernaut but, SHEIN and its’ ultra fast fashion counterparts are certainly not dead.

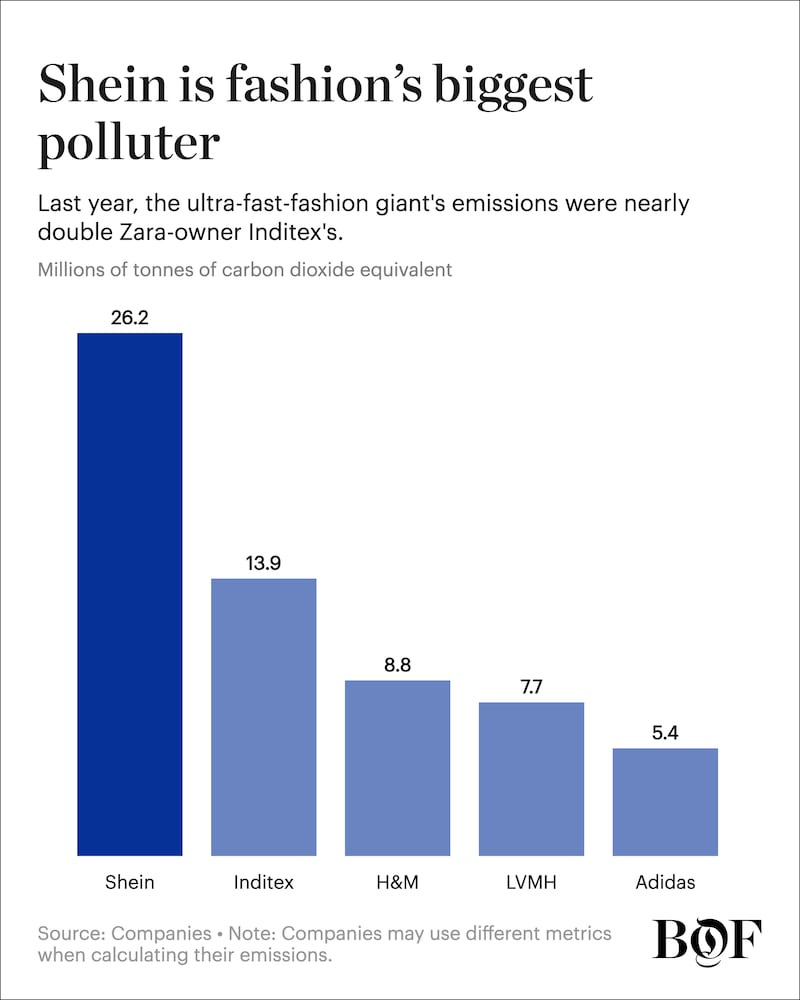

First off, where is SHEIN at from an emissions and impact perspective? They recently published their 2024 sustainability report, reflecting data before de minimis went away. According to the report SHEIN’s emissions jumped 23% last year to hit 26 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. And as my favorite sustainability journalist, Sarah Kent, wrote in Business of Fashion:

“That gives Shein the dubious honour of fashion’s worst polluter for the second year in a row — at least among companies that disclose any data on their environmental impact.”

SHEIN’s sales growth did drop off pretty significantly in early February when Trump made his initial plans for de minimis known, decelerating from 22.0% YoY to 9.6% YoY, according to Earnest debit and credit card data. But then it bounced right back.

Since then, SHEIN and others have raised prices to offset some of the 30% or flat fee incurred by the new duty rate that applies to all products. It’s estimated that the new duty rates on these low price shipments would incur a $10-20 cost per order, effectively destroying the ultra low prices that SHEIN has become known for.

The official end date of de minimis was May 2nd 2025 so we likely won’t see the full impact of this change until Q3 results are reported. SHEIN’s sales slid 23% during the week of April 25 to May 1 compared with the prior seven days and Temu’s daily U.S. users plummeted nearly 48% from March to May 2025. This is significant but still shy of what analysts predicted - they estimated that 30–50% of SHEIN’s U.S. sales (currently ~$8–$10 billion annually) could evaporate almost overnight without de minimis. But fret not, SHEIN and Temu have been quick to pivot to increase their advertising in the EU where a duty-free loophole still exists for shipments under 150 Euros. Also according to Reuters, U.S. ad spend dropped 69% from March to June while SHEIN increased advertising in Europe (France +45%, UK +100%). It remains to be seen if the EU will shut down this exemption in a similar fashion to de minimis.

What’s confusing me is that, amidst all this noise of tariffs and a looming recession, ecommerce sales have been crushing this Spring with no signs of slowing down. I think we all predicted some panic buying ahead of these on-again off-again tariffs so, does that explain it? But what about the price of eggs?! There have been very modest price increases on Amazon from Chinese sellers, according to Reuters: +2.6% between January–mid June, outpacing core goods inflation (~1%), signaling that tariffs are now being passed to consumers. According to this super animated and fun China ecommerce expert, Ed Sander, 75% of all sales on Amazon’s marketplace now come from Chinese sellers. Check out this video if you want to go deep into the madness of cross-border ecommerce from the big 4 (Temu, Shein, Alibaba, Tik Tok Shop).

How so?! A sub 3% price increase on $10 items could likely easily be absorbed by the customer but where’s the rest of that increase? Is there enough margin for the suppliers to absorb the rest of that? I doubt it. I hear that the Chinese government is handing out very attractive loans and financing to manufacturers to keep them afloat during this tariff uncertainty. More on that another day. Another question, are these sellers actually declaring these goods and paying the new duty rates or are they still sidetracking through some sneaky black hat methods?

So what’s the bottom line here for the instant fashion players?

Has Trump done one good thing here by eliminating de minimis? Despite having benefited from de minimis while running Public Habit, I think this loophole needed to go. It has started to level the playing field for ultra fast fashion players and required companies like SHEIN to think longer term about their market strategy in the US i.e. storing goods in the US and paying for bulk shipments. That being said, these duties don’t do anything to minimize the production of polyester and other fossil-fuel derived synthetics that are flooding landfills worldwide. That requires different rules and transparency. According to SHEIN’s sustainability report, polyester made up 81.5 % of their material portfolio in 2024, up from 75.7 % in 2023. WRONG DIRECTION.

What about on-demand production? SHEIN’s “sustainability” claims really do lean on the small-batch, on-demand business model. Surprisingly, I haven’t seen them do any sophisticated analysis on what this means in terms of emissions reduction, water savings etc. Probably because despite producing fewer units/style, they’re still producing more than any other single fashion brand.

That being said, I still think on-demand is not getting the attention - or investment - it deserves. Unspun - the on-demand weaving startup in the US with backing from Walmart - commissioned an LCA study to understand the impact reduction of producing jeans with their Vega machine. Their data showed “approximately 53% and 42% GWP (global warming potential) impact savings compared to similar pants with 70% sell-through rate.” Overproduction is still the elephant in the room and the inherent inefficiencies in the supply chain where ~30% of items made aren’t sold. Business models like SHEIN are so efficient; inventory is supplier-owned and managed until it sells and sell-throughs are near 100%. But it’s all trash.

I’m curious to see how SHEIN (Temu, TTS and the likes) responds and adjusts to a new normal without de minimis. Will customers simply absorb these higher prices? It has certainly hurt the business’ accelerated growth but, if the execution is as good as it is and suppl

Some open tabs this week

An article about the cash liquidity crisis in fashion’s supply chains

Business of Fashion’s unpacking of SHEIN’s latest sustainability report

I really love what Brittany Sierra has created with the Sustainable Fashion Forum. Her substack, Green Behavior, is great for breaking down the weekly mayhem in fashion sustainability news from new partnerships, scandals, policy updates and job postings in the field. Her recent post analyzing sustainable fashion jobs really struck a chord about how competitive and underfunded sustainability teams are right now, especially in the US.

A bit more about me…

I’m a Taurus, ENFJ…hahahahahaha just kidding.

I have spent over 15 years in and around the fashion supply chain starting with quality control in a baby clothing factory in Qingdao, China. I’ve run buying teams, product management and sourcing teams at Fortune 100 companies and have launched a couple of small but interesting fashion companies that set out to flip the supply chain script. I’ve been featured in Vogue, Harpers’ Bazaar and Forbes and I hate that I love that.

I now run Mile One, a boutique supply chain consultancy focused on delivering impact strategies for resilient and equitable supply chains. I really love working with founders and early stage climate tech, fashion and manufacturing companies to help craft big-picture sourcing, supply chain and sustainability strategies. And then implement them. Hit me up if you want to talk!

Tier 1 factories represent the finished goods manufacturer, typically cut and sew in apparel. Tier 2 is fabric mill where the finished fabric is made. Tier 3 and 4 represent stages even further back in the supply chain, yarn spinner and farm/raw material producer respectively.

MOQ: Minimum order quantity. This is often the first frontier of negotiation between buyers and suppliers. Buyers want to produce less for the lowest price possible to minimize exposure. Suppliers want to maximize profit and, typically, they can only get there with scale and high volume orders.

Insightful and deep analysis. Well done.